classroom teaching

Select an item by clicking its checkbox

“This class goes soooo fast!” “Wait, we just started! … It’s over?” “Doc, time in this class flies by.” Recognizing when students are learning and when they are not can be a challenge. The above student comments are the kinds of feedback I yearned to hear. I would listen for ...

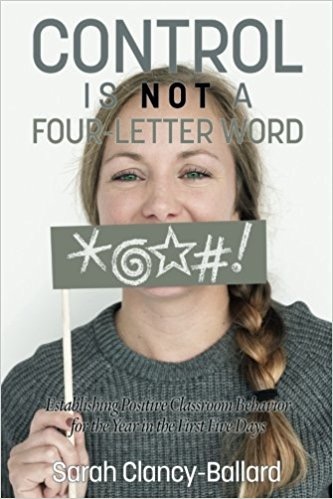

Control is Not a Four-Letter Word!: Establishing Positive Classroom Behavior for the Year in the First Five Days

Date Reviewed: January 23, 2019

Control is Not a Four Letter Word provides an abundance of helpful information for everyone from the first-time teacher to the veteran teacher. After forty years of classroom experience, Sarah Clancy-Ballard bridges the gap between learning how to teach and establishing classroom authority. She believes a teacher sets the tone for the entire year in the first five days of a new school year (xii). The resonating theme of the text is that classroom control emerges from preparation and “the depth of commitment the teacher has to control the class” (xiii). The author examines the importance of first impressions, organizing and utilizing the written word, time management, and behavior management.

Clancy-Ballard’s classroom teaching experience leads her to believe the secret to classroom management is a teacher’s ability to control their classroom when students feel that the teacher cares for them on a personal level (6). The author notes facial expression and remembering student names are the most important things a teacher can to do to set the tone and communicate interest in students as individual people. She values relationship building both inside and outside of the classroom as a vital part of a teacher’s educational philosophy. Clancy-Ballard stresses that teachers need to form relationships with janitorial staff, fellow teachers, and administrative staff, and encourages new teachers to watch “veteran teachers: what works and does not, and how it changes with each principal” (33). She provides a detailed look at how to organize the classroom space, utilize textbooks, handouts, and instructional boards, and create a daily classroom routine. The book covers dozens of examples of routine-driven agendas, inspiring readers to “establish a routine for the beginning of class” (46).

Clancy-Ballard equips the reader with clear guidelines for implementing evaluation methods and time management within the classroom. She associates teacher time management and student assessment to classroom behavior management, pointing once again to the importance of preparation. The author emphasizes that “the student’s attitude about himself or herself and you is directly related to how he or she perceives they are doing in class,” thus connecting the teacher’s behavior to the student’s achievements (55). She encourages teachers to take inventory of their strengths and weaknesses, understanding how their “behavior in class will directly impact the behavior” of their students (66). Clancy-Ballard proposes a benevolent dictatorship approach in the classroom – treating students as intelligent individuals who have ownership of classroom management. By beginning the school year with clear expectations and explaining why the guidelines are instrumental to the class’s success, the teacher can establish control through preparation characterized by benevolent dictatorship (71).

Control is Not a Four Letter Word is primarily written for first-time elementary school teachers; however, it can be a useful reference guide for teachers from elementary through high school. This book is a useful asset for school principals to utilize with teachers for discussion about the numerous reflection questions. This could help ensure appropriate application rises from knowledge.

Professors at the undergraduate level, will find Control is Not a Four Letter Word a helpful tool to assist senior-level students as they leave the classroom and begin student teaching. During the first half of the school year, student teachers would benefit by using the text’s key concepts to observe and evaluate the lead teacher and their level of classroom control. By the second half of the year, student teachers would be well versed in the key concepts, and thus prepared to apply Sarah Clancy-Ballard’s methods in the classroom.

Textbook Gods: Genre, Text and Teaching Religious Studies

Date Reviewed: July 15, 2015

Textbook Gods is a collection of essays by predominantly European scholars of religion on the use of textbooks in primary, secondary, and post-secondary educational settings. Textbooks are understood to be books written primarily for classroom teaching that convey “key knowledge” within a given academic discipline (2). As such, textbooks generally present disciplinary knowledge as stable, firmly established, and definitive. The essays in this volume wrestle, first, with the problems of bias and essentialism in such authoritative, institutionally-sanctioned books. By extension, they also consider the impact of religious studies textbooks in reproducing knowledge of religion in the public sphere. Satoko Fujiwara argues in her essay, for instance, that the religion textbooks used in secular Japanese public schools prioritize world religions over ethnic religions and provide monothetic and essentializing accounts of these religions (for example, Christianity is love, Buddhism compassion, Islam obedience). Likewise, in their contributions James Lewis and Carole Cusack criticize textbooks for validating students’ ethnocentric prejudices about sub-Saharan African religions and aboriginal Australian religions. In a somewhat different vein, Bengt-Ove Andreassen critiques the way that introductory Norwegian textbooks present “religion” as a positive, universal phenomenon that is necessary for human fulfillment and flourishing.

Other essays have a more methodological focus, discussing the ways that scholars of religion can assess religion textbooks, both as teaching resources and as indices of the status of scholarship on religion. Katharina Frank outlines a theoretically-informed methodology for assessing the ways that a new Swiss world religions textbook frames the phenomenon of religion. Mary Hayward surveys the use of visual aids in four textbooks that are used in England’s secondary school religious education courses, tabulating types of images and their relation to the text. She calls for a stronger interrelation between text and image because the privileging of text mirrors the privileging of the intellectual over the material in the study of religion.

The essays in this volume are generally of good quality: they are well written, they fully contextualize the textbooks that they discuss, and they engage contemporary debates in the scholarship of religion (for example, on the public role of religion in secularizing societies; on the utility of “religion” as an analytical category). This volume should not be seen as an aid for teachers of religion who are considering which textbooks to use in their classes. Though the essays in it discuss many different textbooks at length, the primary topic is not their specific merits and demerits, but rather the role of textbooks as a genre in the production of public knowledge of religion. I would strongly recommend this book for experienced scholar-teachers who are reconsidering how they use textbooks, or even if they should use textbooks at all. The range of materials covered by the essays, and the diversity of opinions they present, make Textbook Gods a valuable resource.

Using Reflection and Metacognition to Improve Student Learning: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy

Date Reviewed: December 23, 2014

This collection of essays has its origins in a three-year research project at the University of Michigan (funded by the Teagle and Spencer foundations), which intends to find ways to improve undergraduate education by developing “targeted, exportable classroom strategies to help bridge the gap between students’ and faculty’s (or novices’ and experts’) understanding of disciplinary writing and thinking” (2). Based on research that recognizes metacognition as “most important to good learning outcomes” (2), this collection explores whether disciplinary metacognitive strategies will assist students “to better connect diverse disciplinary writing tasks and develop more versatile identities as disciplinary writers” (3). To that end, they include essays on the use of metacognition in several different disciplines: biology, engineering, mathematics, psychology, humanities, and composition. They conclude that both “student and faculty engagement with course material and writing tasks is resoundingly improved by the introduction of metacognitive strategies” (3).

The basic premise upon which this collection rests is that people can learn how to learn. This generally takes two forms. In the first, students might be asked to “reflect” on their learning, by attending to their discomfort, ambiguity, and uncertainty, and revisiting a learning experience again and again in order to discover new insights and a more sophisticated understanding (6). In the second, students might engage metacognition (thinking about thinking): they establish a plan to learn (for example, make predictions, set aside sufficient time, gather appropriate resources, and decide which approach will be most efficient based on experience), monitor their learning (with self-tests, for example), and evaluate success (their ability to recall the idea a week later). Attention to metacognition facilitates students’ ability to transfer understanding across disciplines.

Teachers in religion and theology might be particularly interested in a number of immediately useable teaching strategies. Consider “exam wrappers”: after giving a test, ask students to describe how they prepared for it; collect their responses, and return them as they begin to prepare for the next test. In this way, students can monitor and evaluate their learning and give their “future selves some advice” (24). Or invite students to monitor their thinking by including comments in the margins on their writing assignments; for example, they might say, “I am not sure I understood how these two ideas connect,” or “I think I have this correctly stated but I may have to check my facts” (122). Or consider inviting students to design a fifteen-week project using a template to identify purpose, audience, context, genre, media, and arrangement strategy; this type of assignment encourages students to make deliberate rhetorical choices and to revise both their design and their product iteratively. Or try this: invite students to “repurpose” their content knowledge in alternative formats (written page, presentation, image, video, blogging, and so forth) in order to develop skills as emerging experts in their profession (178). Each essay provides concrete, practical descriptions of how reflection and metacognition can be used in different disciplines, with abundant samples of assignments, templates, surveys, and student examples.