A Reflection on Learning to Teach and Teaching to Learn

As an educator, I seek to structure learning spaces that are caring, hospitable, and collaborative, nurturing a community of learners in search of truth under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Effective education involves concepts to be shared and critiqued (lectures, readings), cases to be solved (examples, case studies, supervised practice) and values-perspectives to be formed (dialogue, genuine conversations). We teach who we are, and a clear sense of identity in Christ is pivotal. My goal for the programs I lead is to equip pastors and educational leaders for teaching, discipleship, and missional church (Mt. 28: 18-20; Eph. 4: 11-16; Col. 1: 28).[1]

Curriculum Theory & Teaching Implications

“To teach is to have some content and a plan and some strategies and skills, to be sure. But to teach is also to make choices about how time and space are used, what interactions will take place, what rules and rhythms will govern them, what will be offered as nourishment and used to build shared imagination, and what patterns will be laid out for students to move among.” David I. Smith.[2]

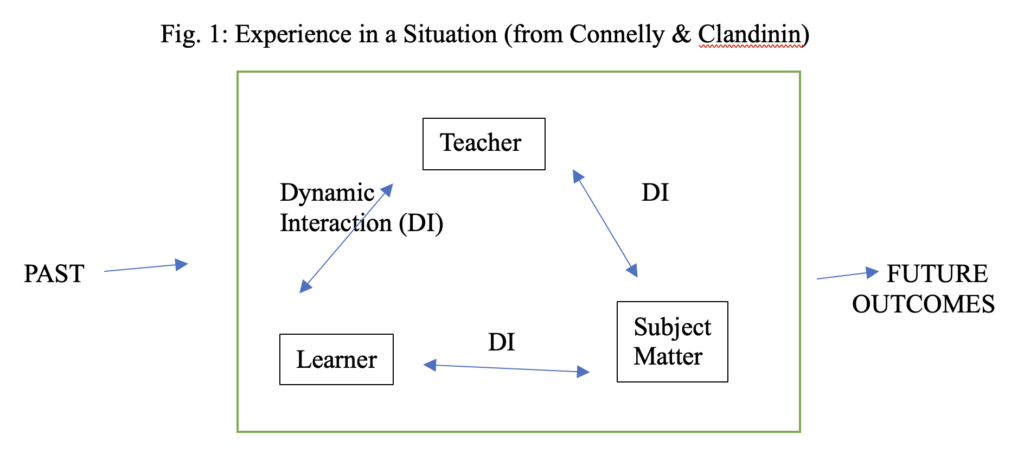

While many view curriculum as a predetermined list of subjects, Elliot Eisner defines it as a series of planned events with educational consequences.[3] Michael Connelly and Jean Clandinin emphasize the significance of "persons," "experience," and "situation" in curriculum. They consider the "teacher" as crucial because curriculum planning hinges on "teacher thinking" and "teacher doing." The teacher's role in orchestrating the interaction between learners and subject matter within a specific context is pivotal. For them, curriculum is something experienced in a particular situation (Fig. 1).[4]

Allan Ornstein and Francis Hunkins view curriculum as comprising four common elements, which corresponds to Connelly and Clandinin. They are: (1) Objectives (outcomes); (2) Content (subject matter); (3) Learning experiences (dynamic interactions between teacher, learner, and subject matter); (4) Evaluation (quality of experience; achievement of outcomes). They emphasized that how these parts are arranged are never neutral.[5]

Teaching as Structuring Learning Space and Developing Engaging Experiences

Before I review the syllabus and requirements, I begin every course with a lecture, “Covenant, community and a culture of learning,” which outlines the values that structure my learning space, some basic educational theories, and need for active learning.[6]

My values are as follows: (1) Care; (2) Hospitality; and (3) Community.[7]

Care - Students begin by sharing their backgrounds, concerns, and hopes for the course. They use name cards for personalized interactions. [8] In online classes, students complete “our learning community" forum. I offer a personal welcome and use this information for weekly prayers for students. I also have a forum for prayer requests.

Hospitality - Students are encouraged to be open to new ideas from readings, lectures, and group discussions. They are to listen to one another, promoting “genuine conversation.” [9]

Community - I emphasize collaboration, not competition. I have invited each class to my home for a community meal since 2001 (until Covid-19 restrictions).[10]

At the end of the course, students reflect on the values that structured their learning spaces and shaped their practices. My question is, are these educationally and theologically sound?[11]

Learning as Participation in a Community of Truth

“In its briefest form, the model asks teachers to consider how to see anew, choose engagement, and reshape practice” (author’s emphasis). David I. Smith.[12]

“The hallmark of the community of truth is in its claim that reality is a web of communal relationships, and that we can know reality only by being in community with it” (author’s emphasis). Parker Palmer.[13]

Mortimer Adler's Paideia Proposal consists of three key elements: didactic instruction for acquiring organized knowledge, coaching to develop critical thinking skills through problem-solving, and Socratic dialogue for deeper understanding through active discussions.[14] Parker Palmer critiques the "objectivist myth of knowing" and advocates for a "community of truth" where both experts and amateurs gather around a subject, guided by shared rules of observation and interpretation. Rather than absolutism or relativism, he encourages openness to transcendence with the practice of "educational virtues."[15]

Some things I do in my classes:

- Introduce concepts through didactic instruction, with Socratic dialogue to illuminate the frameworks of understanding within which students operate. Jesus practiced both in his teaching ministry.[16]

- Facilitate and invite diverse viewpoints; encourage students to ‘embrace ambiguity.’ Often, the result is more questions than answers, but part of my work is to challenge the ‘objectivist myth of knowing.’[17] I adopt the “constructivist model” in teaching, which according to Mayes and Freitas, is most suited to seminary education (see endnote 15).[18]

- Case studies often spark good conversations, revealing the complexity of ministry. In INTD 0701: Internship, students present cases and we reflect biblically and theologically together in “ministry reflection seminars.”

- Assignments match learning outcomes, and encourage critical engagement with key texts and articles, with thoughtful applications.

- Carefully curate a “resource” section on Moodle for every course so students can explore related and updated research for further learning.

Person of the Teacher & Teaching as Spiritual Act

The goal of theological education is “the acquisition of a wisdom of God and the ways of God fashioned from intellectual, affective, and behavioral understanding and evidenced by spiritual and moral maturity, relational integrity, knowledge of the Scripture and tradition, and the capacity to exercise religious leadership.” Daniel Aleshire.[19]

This book builds on a simple premise: good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher (author’s emphasis). Parker Palmer.[20]

Jesus condemned the religious teachers for their hypocrisy (Mt. 23: 1-36). In this context, Jesus cautioned against accepting undue accolades (v8) or putting teachers on “pedestals” (v9). God is our only Father; the Messiah is our only teacher (vs 9,10). James cautioned that not all should be teachers because teachers would face stricter judgment (Jas. 3:1-2).

As I endeavor to form pastors and ministry leaders not just with the wisdom of God, but with spiritual, moral, and relational integrity, here are some things I emphasize:

- Each class begins with a short Bible meditation; the class responds with sharing and prayer.

- Convinced that transformation is ultimately the work of the Spirit, I pray for my students as I prepare for class each week.

- I have a lecture entitled: “The person of the teacher and teaching as a creative, spiritual act” in CHED 0552: Learning to Teach; Teaching to Disciple. Since curriculum planning rests largely on “teacher thinking” and “teacher doing,” students present their “teacher chronicles” in CHED 0652: Curriculum Design for Learning & Discipleship to better understand their education and discipleship values.[21]

- We are fearfully and wonderfully made (Ps. 139:13-16; Eph. 2:10). We should know our gifts (and limits), and the dangers of ministering out of a “false self.” I also emphasize the crucial role self-care holds in ministry.[22]

- Palmer notes: “Good teachers possess a capacity for connectedness. They are able to weave a complex web of connections among themselves, their subjects, and their students so that students can learn to weave a world for themselves.”[23] I am vulnerable to share both “joys and failures” in ministry, and constantly seek to “join self, and subject and students in the fabric of life.”[24]

Notes and Bibliography

[1] Graham Cray notes that “… a church is a ‘future in advance’ community … modeling and ministering an imperfect foretaste of the new heaven and new earth.” Quoted in Alison Morgan, Following Jesus (2015), 159. Edie and Lamport provides a succinct vision for Christian Education: “… [T]he preeminent task of Christian educators is to assist persons with (re)establishing their relationship to divine love, to connect biblical truth to life, to participate intimately in a community of faith, to examine their cultural surroundings in light of kingdom values, to embrace the call to obedience and sacrifice, and to critically reflect about God in the world, and in doing … to discover blessing in ‘the tie that binds’ to God, neighbor, and creation.” Fred P. Edie and Mark A. Lamport, Nurturing Faith: A Practical Theology for Educating Christians (Eerdmans, 2021, p. 24)

[2] David I. Smith, On Christian Teaching: Practicing Faith in the Classroom (Grand Rapids, MI.: Wm. E. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2018), 19.

[3] Elliott W. Eisner. The Educational Imagination: On the Design and Evaluating of School Programs, 3rd edition (Upper Saddle River, NJ.: Merrill Prentice Hall, 2002), p. 31.

[4] F. Michael Connelly and D. Jean Clandinin, Teachers as Curriculum Planners: Narratives of Experience (Toronto/New York: OISE and Teachers College Press, 1988), 6-10.

[5]Allan Ornstein and Francis Hunkins, Curriculum: Foundations, Principles, and Issues. 7th edition (Pearson Education, 2017), 161. For example, depending on teachers’ views of learners (“receptacles” or “critical inquirers”), teachers would adopt different teaching approaches.

[6] Eisner speaks of three curricula: “explicit, implicit and null.” While the “explicit curriculum” is the conscious intentions in the syllabus, the “null” is what is left out in a course. The “implicit curriculum” is a teacher’s values that determine educational procedures and create distinct classroom cultures. Eisner notes that this is often overlooked, but impacts learning significantly. Eisner, Op. cit., chapter 4.

[7] Yau Man Siew, “Fostering community and a culture of learning in seminary classrooms: a personal journey,” Christian Education Journal, 3,1 (2006), 79-91. Since this publication, I have revised my lecture “Learning Covenant, rev. 2023” with updated research.

[8] Carol Holstead asked 80 students in an open-ended survey what made them feel that a professor was invested in them and in their academic success. The number 1 response was “when the professor learned their names.” Carol Holstead, “Want to Improve Your Teaching? Start With the Basics: Learn Students’ Names,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Sept. 11, 2019. It is interesting that these “softer elements” are gaining attention in higher education. See John P. Miller, Love and Compassion: Exploring Their Role in Education (University of Toronto, 2018).

[9] David Tracy notes that theological study involves “genuine conversation,” and the “hard rules” of genuine conversation require us “to say only what you mean; say it as accurately as you can; listen to and respect what the other says, however different or other; be willing to correct or defend your opinions if challenged by the conversation partner; be willing to argue if necessary, to confront if demanded, to endure necessary conflict, to change your mind if the evidence suggests it.” David Tracy, Plurality & Ambiguity: Hermeneutics, Religion, Hope (Harper & Row, 1987), chapter 1. Stephen Brookfield highlights that because adult cognition involves embedded logic, dialectic thinking, and epistemic cognition, it is imperative to create safe and hospitable spaces for them to share their experience, engage in critical reflection and debate. For adult learners, difference is good, even desirable. Stephen D. Brookfield, The Skillful Teacher, 3rd edition (Jossey-Bass, 2015).

[10] Since the church is the body of Christ, we practice “community” now. In Summer 2023, I taught an intensive, in-person course and invited 19 students home for a community meal. The impact on student dynamics was significant. David I. Smith notes: “I suspect that one of the most important Christian practices that might sustain Christian teaching and learning is intentional community, learning continually with others and from others how to live out our vocation to be the body of Christ.” David I. Smith, Op. cit., 158.

[11] David K. A. Smith notes that “behind every pedagogy is a philosophical anthropology.” David K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom (Grand Rapids, MI.: Baker Academic, 2009), 27-28. Also, David K. A. Smith, You Are What You Love (Grand Rapids, MI.: Brazos Press, 2016), 126-128. David I. Smith encourages us to reflect on “how our faith might shape pedagogy demands that we see our classrooms anew, letting a Christian imagination supplant mere devotion to technique” (author’s emphasis). David I. Smith, Op. cit., 149.

[12] David I. Smith, Opt. cit., 82. Smith discuss these three aspects in detail, with many helpful examples in chapters 7-10.

[13] Parker Palmer, The Courage to Teach, 20th anniversary edition (San Francisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass, 2017), 97.

[14] Mortimer Adler, The Paideia Proposal (Touchstone, 1998). It is interesting that Adler’s Paideia has similarities to the three models proposed by Mayes and Freitas: The “associationist model” (learning as the gradual building of patterns of associations or skill components through memorization, drill and practice), the “situative model” (placing learners within “communities of practice” where experienced peers help novices acquire habits, values, attitudes and skills) and the “constructivist” model (teachers help learners construct a cognitive framework so they can evaluate competing claims to truth and defend their intellectual commitments). Mayes & S. de Freitas, “Technology enhanced learning: The role of theory” in Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age, Editors. H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Routledge, 2013), chapters 1, 13.

[15] These virtues include welcoming diversity, embracing ambiguity, creative conflict, practice of honesty, humility, and freedom. Parker Palmer, The Courage to Teach, 20th anniversary edition (San Francisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass, 2017), 102-111. Paolo Freire calls the “banking” model oppressive and violent; instead, he calls for “problem-posing” education where instructor and learners are “co-investigators” engaged in critical thinking in a quest for mutual humanization. Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1970), 73.

[16] While Jesus taught formally (Mt. 5:1-2; Lk. 7:28-29), his common method was informal with question & answer, dialogue, debate, observation, and reflection amid life. His parables were deliberately puzzling and opaque, demanding his hearers to make the mental effort to penetrate the surface to get deeper, spiritual meaning and find their place in the story. Keith Ferdinando, “Jesus, the Theological Educator,” Themelios 38, issue 3 (Nov. 2013).

[17] Once at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, two NT professors debated “the place of women in the church.” They argued using the same passages but came to different conclusions.

[18] While I adopt the “constructivist model,” I am eclectic in my educational philosophy. In a “Find your educational philosophy” test in David M. Sadker & Karen Zittleman, Teachers, Schools & Society, 5th edition (McGraw-Hill College, 2017), I scored high in “perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, social reconstructionism.” For a helpful overview of these philosophies, see Tables 1.1 and 1.2 in Allan C. Ornstein, Edward F. Pajak, and Stacey B. Ornstein, Contemporary Issues in Curriculum, 5th edition (Pearson, 2011), 6-7. In CHED 0551/CHRI 2213: Educational History & Philosophy and CHED 0652, I highlight strengths in each philosophy, critique them from a theological perspective, with implications for education in the church and academy.

[19] Daniel Aleshire, Beyond Profession: The Next Future of Theological Education (Eerdmans, 2021), 73.

[20] Palmer, Op. cit., 10.

[21] Since the person of the teacher is most important in curriculum planning, Connelly and Clandinin encourage teachers to develop their “teacher chronicles,” narratives of key influences which shaped their teaching values. Connelly likely learned this from his doctoral mentor, Joseph Schwab at the University of Chicago. Cheryl Craig, "Joseph Schwab, self-study of teaching and teacher education practices proponent? A personal perspective," Teacher & Teacher Education 24 (2008), 1993-2001.

[22] To better understand “false self vs. true self,” see James Martin, S.J., Becoming Who You Are (HiddenSpring, 2006). For self-care in ministry, see Matt Bloom, “Building Vibrant Ecologies for Pastoral Wellbeing,” Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry (May 2022), 7-20.

[23] Palmer, Op. cit., 11.

[24] Palmer, Op. cit., 11

Due to word limit I could not include my “postscript.” Here it is:

Horace Mann (1796-1859), a great American educational reformer, slavery abolitionist, and politician committed to promoting public education (known as “The Father of American Education”) said: “Teaching is the most difficult of all arts and the profoundest of all sciences.” Jonathan Messerli, Horace Mann: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 37.

I have had good and bad days in many classes (and still do). While I have matured over the years, I resonate strongly with David I. Smith who said:

“There is no quick recipe for Christian pedagogy, just a long process, worked out with fear and trembling, of taking off the old and putting on the new, and finding ways of speaking, acting, and shaping shared activity that resonate with the kingdom of God. It is born of prayer, of study, of listening to students, of the acquired discipline of attentiveness to what is happening in class, of the humility that allows us to hear from others that our best efforts are not quite doing what we think they are.” David I. Smith, On Christian Teaching: Practicing Faith in the Classroom (Grand Rapids, MI.: Wm. E. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2018), 158.