Reflections on Racism, Shame, and the Complexity of Human Nature

Before I address the racism I experienced at Columbia Theological Seminary, I would like to introduce myself to those reading this. My name is DeNoire Henderson, I am a 26-year-old African American woman born and raised outside of Atlanta in two small towns, Stone Mountain and Snellville, GA. I received my B.A. in Communications and Culture from Howard University with a minor in Political Science. Before attending Columbia Theological Seminary, I spent three years teaching at a predominately Black and Hispanic school. My formal education from Howard University, personal experience teaching in the classroom, and my grade school education in a predominately white school district taught me the importance and impact of seeing yourself in the learning materials. There are hundreds of studies on the critical nature of increasing cultural diversity in classroom materials so that students “see themselves.” It is important that students’ cultures are represented, but it is equally, if not more important, how they are represented.

During my time at Howard, I wrote a thesis on the indoctrination of inferiority and superiority complexes by television news media. Through my research, I discovered just how much representation impacts personal, social, and cultural identity. The scope of my work was limited to the impact of television news media, specifically, FOX News. However, my experience in education taught me that indoctrination in the classroom is just as powerful, maybe more so.

In 2020, the world went through an incredibly difficult year. We were living through a global pandemic and suffering from all of the side effects: fear, trauma, sickness, grief, doubt, lack, depression, etc. Amid this, the world watched a defenseless black embodied man be murdered in broad daylight. We watched cities destroyed in the aftermath and continued to have the event replayed in our hearts, minds, and screens. As a black woman, this trauma ate away at me as I tried to find joy, peace, and community amongst my friends, family, and classmates while in isolation. Due to the nature of the pandemic, I saw my professors and classmates through zoom screens more than I saw my own family and schoolwork became one of the only constants in my life. Amid this, I received a letter from Columbia Theological Seminary in June of 2020 acknowledging their historical contribution to the oppression of those that look like me, stating they would be working to “repair the breach.” While I was proud of my institution for taking the stance of standing with me and those who look like me, I was not foolish enough to believe that the racism embedded in this institution would disappear overnight. However, I did feel safe enough to share my pain and hopeful about the potential healing that could happen in this place. Then, just eight months later, something happened that both shocked and rocked me to my core.

In February 2021, during a theology lecture, my professor, Dr. Martha Moore-Keish, uploaded a lecture for the class to watch on the four stories of humanity.

“First of all, I wanted to frame this week in terms of how it stands in relationship to the whole course and think about the concept of sin, and why it’s still something that is worth considering. The purpose of thinking about this concept of sin is simply to name as clearly as possible the alienation between ourselves and God. To name the brokenness of the world that has to do with the suffering of our relationship between ourselves and God and has to do with our harm that we do to ourselves, to one another, and to the world.”

She then went on to share her screen to display images to help us see the four stories of humanity.

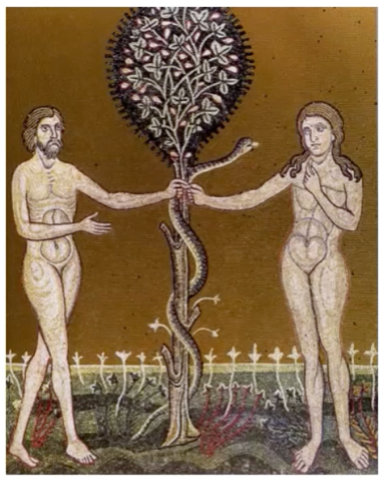

This is the image she displayed to illustrate “what it means to be created beings, human beings as creatures created good and in the image of God. Creatures who are made in the image of God, who are also fully embodied. (12th-13th century Mosaic of Adam and Eve, Cathedral of the Assumption, Monreale, Sicily: https://www.christianiconography.info/sicily/originalSinMonreale.html)

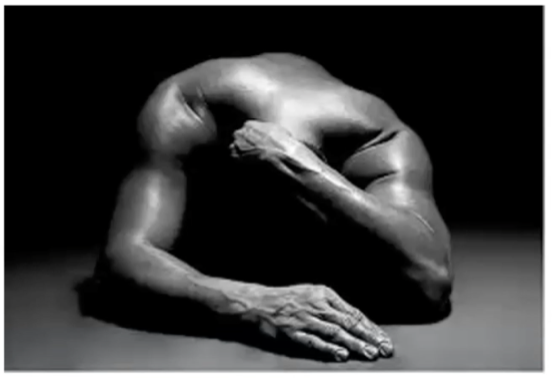

This is the image that was used to illustrate “humanity as sinful having turned away from relationship with God therefore alienated from God’s intentions from the world and from our own well-being.” (PowerPoint Slide of Dr. Martha Moore-Keish, public domain source unknown)

This is the image used to illustrate “humanity as redeemed by God and Jesus Christ, drawn back into covenant relationship and made new.” (“The Return of the Prodigal Son” by Rembrandt (ca. 1667-1669): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Return_of_the_Prodigal_Son_(Rembrandt))

This is the image used to illustrate “human beings as oriented toward a future hope of perfect communion with God and with one another.” (“The Peaceable Kingdom” by Edward Hicks (1834): https://www.wikiart.org/en/edward-hicks/peaceable-kingdom-1834)

She then ended this portion of the lecture by saying, “So this just visually I hope reminds you of what we’re looking at over the course of the entire semester and to locate this week in the context of those four stories, now. This concept of sin has, I think we need to acknowledge, been harmful at some points to some people in human history, and so we need to acknowledge this.”

In light of all that had transpired for me and was still transpiring for me, I saw my theology professor perpetuating the ideologies that made it possible for George Floyd to be murdered in the street. Black bodies represent “humanity as sinful having turned away from relationship with God therefore alienated from God’s intentions from the world and from our own well-being.” In isolation, the use of the black body to represent sin is not really the problem. This image juxtaposed with the other images of white bodies representing good, redeemed, and perfect humanity is the problem. I immediately closed my computer, too upset to finish the assignment. I screen recorded the lecture later that evening and sent it to other colleagues (some at Columbia and others studying and teaching elsewhere). I asked them to tell me what they saw, before telling them what I felt watching it. They all immediately saw the same thing. Some were as upset as I was, some were more upset, and still some more were apathetic, stating that they didn’t expect anything different from white people. “White people are incapable of seeing or being anything but racist.”

I, however, refused to accept this as the norm. I was a student at a school committed to “repairing the breach.” I was being educated by professors who used culturally diverse theologians in their lectures, who attended marches, and wrote about decolonizing Christianity and dismantling Christendom. I would be lying if I said that the event did not make me angry. I was furious because my “well-meaning progressive white professor” was so insensitive to my soul embodied in black skin. However, this anger was not without purpose. It fueled a righteous indignation that forced me to speak up and email my professors. They were very receptive, and apologetic; however, Dr. Moore-Keish’s response (and current reflection) revealed that we have so much more work to do. She told me that she was blind to it and had been using the same images for several years.

My anger then turned to sorrow for her, for the church, and for humanity. How deeply did racism have to be imbedded in such an educated being for them to miss this? She, the professor, the driver of the vehicle of our theological education, who had driven hundreds of students before us, was blindly leading. As I mentioned earlier, because of my formal education I am keenly aware of the value of my black body. I am keenly aware of the lies present in every level of our education system and society at large that tells me black is bad while white is good. My view of myself was not swayed by this distorted portrayal. However, I hurt for those who, like my professor, have not had their lens corrected and are leading others with blind spots that could be deadly. This situation is so much bigger than me, Dr. Moore-Keish, or Columbia. This zoom session represents a microcosm of a human issue.

Dr. Moore-Keish rightly discussed the truth that our sin causes pain. I have reflected upon this for months and realize that while our sin does hurt others, it hurts us more than it ever could hurt others. While I walked away from this situation with more intentionality in how to pray that blind eyes be opened and hearts be changed, Dr. Moore-Keish walked away with shame. As she mentioned, many times, shame paralyzes us. In the following class, Dr. Moore-Keish didn’t even feel that she could pray to lead the class, her guilt and shame were that heavy. However, the sin of racism does not have the final say and neither does the shame that sin brings with it. I prayed to open class, not because I felt lofty and holier than though, but because I could see clearly. In this painful situation, I saw the grace of God and the blood of Jesus. I saw the cross. The heavy cross that looked like defeat to the natural eye but was truly victory. I saw an opportunity for generations coming behind me and everyone connected to those in this grief-stricken virtual classroom to learn the truth because of the cross that we came to in February 2021. Thank God for Jesus and the freedom of the cross that has the power to turn shame into surrender and surrender into sanctification. It is nothing but the redemptive power of Jesus that created the opportunity for us to write together about this event for the sake of helping and freeing others. The Bible says, “Confess your sins one to another and pray for each other so that you may be healed.” We are forgiven in Jesus but healed in community. A few verses before this text says, “And the prayer offered in faith will restore the one who is sick. The Lord will raise him up. If he has sinned, he will be forgiven” (James 5:15). So, we must confess, speak about the event, and pray for one another. Yet, there is another scripture that speaks about the activity of faith. “Faith without works is dead.” We can pray for racial reconciliation and the dismantling of racism until we are blue in the face, but we also must work to discern and avoid perpetuating systems that we are blincaud to.

The work cannot stop with this reflection. Reflection must be continual and communal. It must be transparent to be transformative. It must be vulnerable to be valuable. It must be consistent to be effective. All of this would be in vain if this reflection is the only result. Education must continue, but not unchanged, unchecked, or unchallenged. Checkpoints must be implemented. Curriculum must be reviewed and revised, and not just in the imagery, but in the texts assigned, the examples used, etc. Is that more work for professors? Absolutely. But it is also more work for the disadvantaged. I type this paper after a long day of work, during my summer break, not because I want to add to the shame of my professor or pump my pride. It would’ve been easier for me to decline to speak about the event again. However, I have sight and feel obligated to walk alongside blind people who are trying to see because there are nations and generations following behind us that shouldn’t have to fall into the same pits we have.

This moment was not about pictures any more than the crucifixion was about trees. The tree made the wood out of which the cross was constructed upon which my Lord was crucified. The cross was a mirror that showed the world its sickness and shame which the Lord died to redeem. Many saw a naked savior and felt defeat: Jesus felt the pain he bore but knew of the coming victory. He did not focus on the cross but made his focus the coming redemption. He did not become angry with the ignorant who nailed him to it but rather prayed, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” So, I won’t make this about the racist pictures we encountered upon the hill of theological education, because Jesus did not make his crucifixion about the cross. Instead, I will focus on the coming redemption and pray, “Father, forgive Martha, for she knew not what she did.” I will then accept and magnify the redemptive power of Jesus that was offered up when Christ arose from the dead as we rise from this. Sin was not eradicated when Christ rose, but the paralyzing power of the shame it brings was.

*Read the accompanied blog by Dr. Martha Moore-Keish HERE

Amazing article. I really enjoyed it. It is really presented beautifully.