Teaching the Significance of Sufism and the Arts

In my last two blogs, I have been sharing some thoughts on teaching Sufism and contemporary Sufism, giving special consideration to the importance of helping students actively explore different elements of Sufi tradition and culture in the different Islamic periods. For this blog, I would like to point out opportunities to teach about Islamic arts from Sufi perspectives in order to provide a taste of Sufism’s impact on Islamic cultures and societies. Focusing on the arts allows the student to learn that Sufis frequently sought more artistic means of expression, including poetry, architecture, music, and calligraphy, in order to transcend the conventional language of theology and philosophy which too often fails to prove an adequate means of communicating higher truths. From Sufi perspectives, the arts embody metaphysical principles in visual and auditory forms, communicating these principles with an immediacy difficult if not impossible to achieve within the discursive confines of prose. Additionally, the arts have further functioned as a means to express the simultaneous unity and diversity of Islamic civilizations, as they communicate principles shared by all Muslims, and yet these principles are expressed through diverse cultural themes and motifs, illustrating the confounding array of cultural forms found within Islam.

The profound influence of Sufi poetry, whether it be in Persian, Arabic, Somali, Urdu, or Turkish to  name a few languages, is essential to discuss with students. For many Sufis (e.g., Rumi, Ibn al-Farid, al-Hallaj) poetry was the peak of eloquence and culture for expressing the vicissitudes of human life. By evoking perennial realities such as death, time, and change, poetry brings us into contact with our own existential limitations. In particular, by exploring the poetic works of different Sufi personalities, the student becomes familiar with a variety of Sufi themes, principles, practices and experiences. Studying Sufi poetry and the many poetic techniques (metaphorical language, rhythmical patterns, etc.) then helps the student to understand Sufi symbolism and the idea that the Sufi poet was endowed with the ability to penetrate the veil of appearances in order to depict the essential character of the image being portrayed. In other words, poetry becomes a vehicle to decipher the signs of the Divine.

name a few languages, is essential to discuss with students. For many Sufis (e.g., Rumi, Ibn al-Farid, al-Hallaj) poetry was the peak of eloquence and culture for expressing the vicissitudes of human life. By evoking perennial realities such as death, time, and change, poetry brings us into contact with our own existential limitations. In particular, by exploring the poetic works of different Sufi personalities, the student becomes familiar with a variety of Sufi themes, principles, practices and experiences. Studying Sufi poetry and the many poetic techniques (metaphorical language, rhythmical patterns, etc.) then helps the student to understand Sufi symbolism and the idea that the Sufi poet was endowed with the ability to penetrate the veil of appearances in order to depict the essential character of the image being portrayed. In other words, poetry becomes a vehicle to decipher the signs of the Divine.

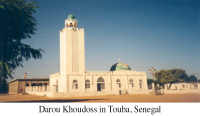

Architecture is also another artistic tradition that can help students consider how the sacred principles of Sufism took material form in structure, with the shrines of saints and Sufi lodges as well as  mosques. These architectural wonders would define the great Islamic cities, while also leaving imprints on the surrounding, expansive countrysides. Students appreciate exploring how these structures were carefully constructed utilizing sacred geometrical principles, symbolic forms and ornamentation, color theory, and sacred calligraphy. Ultimately, many of these structures were created to communicate higher realities and Sufi cosmologies.

mosques. These architectural wonders would define the great Islamic cities, while also leaving imprints on the surrounding, expansive countrysides. Students appreciate exploring how these structures were carefully constructed utilizing sacred geometrical principles, symbolic forms and ornamentation, color theory, and sacred calligraphy. Ultimately, many of these structures were created to communicate higher realities and Sufi cosmologies.

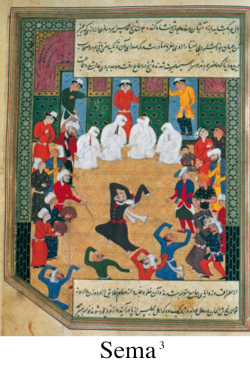

These sites within the built environment were also the places where one of Sufism’s most iconic artistic forms took shape, the various sorts of chant and music developed by different Sufi orders. Each order would develop its own liturgy of chant, with particular formulas, breathing techniques, musical accompaniment, and even dance, reflecting the particular lineage and ethos of the order.

By focusing on the significance of architecture, students learn that Sufi shrines and lodges and mosques of Muslim societies were pivotal sites around which Muslim culture revolved and evolved, where dervishes and sultans, devotees and those seeking healing, all came to participate in the presence of the sacred atmosphere they encountered at these sites. In many cases structures built for trade and residence would radiate outward from centrally located sacred spaces, visually representing the concept of the qutb, the Muslim saint who watches over a particular region. Shrines and lodges integrated local cultural architectural forms, making African and Asian as well as Arab and Persian architectural styles (to name just a few) integral parts of Islamic architecture more broadly.

By focusing on the significance of architecture, students learn that Sufi shrines and lodges and mosques of Muslim societies were pivotal sites around which Muslim culture revolved and evolved, where dervishes and sultans, devotees and those seeking healing, all came to participate in the presence of the sacred atmosphere they encountered at these sites. In many cases structures built for trade and residence would radiate outward from centrally located sacred spaces, visually representing the concept of the qutb, the Muslim saint who watches over a particular region. Shrines and lodges integrated local cultural architectural forms, making African and Asian as well as Arab and Persian architectural styles (to name just a few) integral parts of Islamic architecture more broadly.

Finally, exploring the world of Quranic calligraphy and its influence on Sufism also helps students appreciate some very abstract metaphysical understandings. For many Sufis this practice of writing the sacred word took on added levels of significance, encouraging them to play a very active role in the development of Quranic calligraphy. They experienced calligraphy as an attempt to communicate spiritual truths and realities. In their pursuit of calligraphy, Sufis emulated the broader norm within Islamic culture to give deep respect to the capacity of the written word to convey revealed truths. They regarded Quranic calligraphy as a holy art that offers baraka (blessing) to the recipient of its beauty and wisdom. They contemplated not just the divine words and chapters in themselves, but also the Arabic letters as constituent elements of divine speech. The practice of calligraphy thereby became integrated with other methods of Sufi practice and included reflection on sacred and symbolic qualities of Quranic words.

When sharing the significance of Sufism and the arts, it is important to emphasize how this deeply aesthetic orientation of Islamic culture is rooted in the Qur’an itself, which expressed ethical and metaphysical principles with rhythm and rhyme. This divine beautification of the word would be emulated by Muslims, for whom the word was central to artistic expression. The Quranic word then was beautified aurally in recitation, and visually in architecture, calligraphy, and crafts. This beautiful expression of the word further functioned to inspire divine remembrance, as the linguistic signs of God surrounded Muslim daily living. For many Sufis then any artistic expression, like poetry, architecture, and calligraphy, was a contemplative discipline, the practice of which was a form of dhikr, the art of remembering the Divine.

1. ‘I believe in the religion of love’

This calligraphic piece by Hassan Massoudy is a saying by Ibn al-‘Arabi from his book of poetry, Interpreter of Desires: ‘I believe in the religion of love, wherever its stages may go, love is my religion and faith.’ Hassan Massoudy, a native of Najef, Iraq, is a world-renowned master of contemporary Arabic calligraphy whose works bring light to a variety of classical Sufi personalities and their well-known sayings. To see more of Hassan Massoudy’s artwork visit http://www.massoudy.net.

2. Darou Khoudoss in Touba, Senegal

Darou Khoudoss, “the Abode of the Holy,” is a mosque that was built in the place where Ahmadu Bamba, leader of the Muridiya Sufi order, experienced spiritual retreats and received mystical visions. This photo was taken by Dr. Eric Ross. For more about Ross’ research see https://ericrossacademic.wordpress.com/.

3. Sema

A watercolor painting in the Shirazi style (c. 1582) depicting a sema. This picture is notable in that four women and a child are part of the Sufi circle, suggesting their initiation into the practices of the order.

Source credit: https://the.ismaili/ismaili/fr/london-exhibition-provides-insight-life-and-legacy-prominent-persian-ruler

Leave a Reply