Seeking Awe and Wonder

I remember the first time I felt a sense of awe and wonder about theology. It was in my required Problem of God class at Georgetown University, where I received my undergraduate degree. I had picked a section of the course based on my interest in a list of readings provided with the registration materials the school sent me before I started my freshman year. The professor of that course turned out to be Fr. Thomas King, SJ, who had a reputation as an excellent teacher—something I had no idea about at the time I signed up for the course. I do know I was very fortunate to have done so as my friends who wanted to take his class in the following semester often had trouble finding a spot in his classes.

At this point—over twenty years later—I remember little of the specific content of that class, but in terms of overall structure, Fr. King had basically divided everything into groups of three. We examined a variety of readings—from Augustine to Sartre—and Fr. King’s lectures helped us to understand the way each reading explained the nature of God. In the final class of the semester, Fr. King reviewed all the previous content, illustrating how each author’s approach to God (even Sartre!) could fall into one of three categories of ways of talking about God—ways that ultimately could be thought of as an understanding of God as the Father, an understanding of God as the Son, and an understanding of God as the Spirit. As everyone packed up on that final note, my friend Mike and I sat in our seats, completely dumbfounded. Mike turned to me and said, “He just solved the problem of God.” In that moment, for me, a spark had been lit. I had a sense of awe and wonder about the concepts we had examined, and I wanted more of that sense.

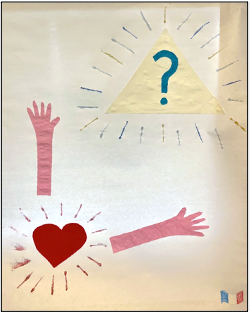

In this piece, I aimed to get at a representation of this spark of awe and wonder. The triangle represents the mystery of the divine—a triangle to represent the Trinitarian God of my tradition of Christianity, with a question mark to show how humans, in this life, can never fully know or understand the divine. The heart is meant to represent the sense of awe and wonder that I feel. I would describe it as a sense of joy burning in my heart—similar to the language Blaise Pascal used in his “memorial,” a description of a mystical experience he had that is often published as part of his Pensées, and echoing, of course, Augustine’s idea of the restless heart. The hands are meant to represent my continued seeking of that awe and wonder in my study and research.

In this piece, I aimed to get at a representation of this spark of awe and wonder. The triangle represents the mystery of the divine—a triangle to represent the Trinitarian God of my tradition of Christianity, with a question mark to show how humans, in this life, can never fully know or understand the divine. The heart is meant to represent the sense of awe and wonder that I feel. I would describe it as a sense of joy burning in my heart—similar to the language Blaise Pascal used in his “memorial,” a description of a mystical experience he had that is often published as part of his Pensées, and echoing, of course, Augustine’s idea of the restless heart. The hands are meant to represent my continued seeking of that awe and wonder in my study and research.

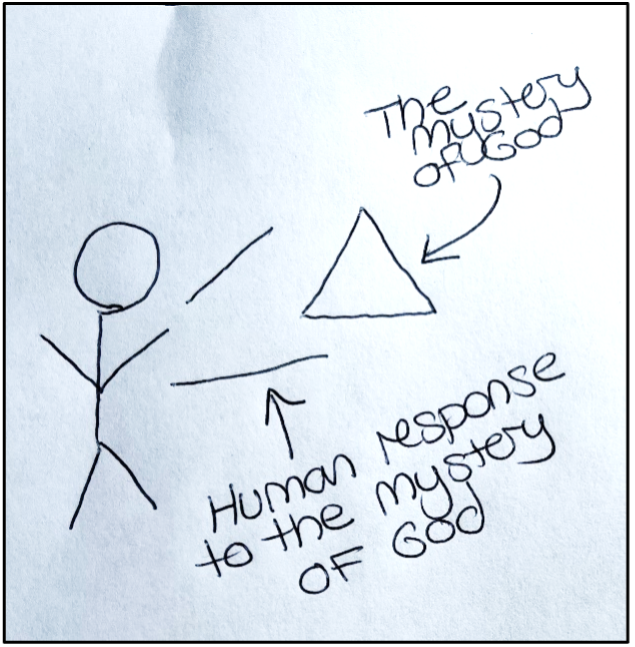

After creating this, I realized that my imagery had unintentionally mirrored a drawing that one of my other undergraduate professors, Fr. Otto Hentz, SJ, used to draw on the board. In my senior year, I happened to meet an alum who told me this image was all I needed to know in Fr. Hentz’s class—that the triangle represented the mystery of God and the two lines represented the human response to the mystery of God. I recall a bit more discussion in Fr. Hentz’s class about our reading assignments, but his lectures almost always included a reference to this image.

When I first considered graduate studies in theology, these Jesuits were the model of the teacher that I wanted to be—one who narrates the content through lecture to try to amaze my students and thus produce the same spark of awe and wonder in my students that had struck me so many years previously. However, I eventually drew on a different undergraduate experience of awe and wonder as a model for my teaching—the experience of reading Pascal’s Pensées in French while studying abroad in Strasbourg, France. This was in the context of a sixteenth- and seventeenth-century French literature course, not a theology course, but as I read and interpreted the text for myself in that context, I found a sense of profoundness and truth in what Pascal wrote. For example, one of my favorite fragments states, “Why do you kill me? What! do you not live on the other side of the water? If you lived on this side, my friend, I should be an assassin, and it would be unjust to slay you in this manner. But since you live on the other side, I am a hero, and it is just” (fr. 293). This fragment really illustrates the absurdity of the ways we divide and separate our human family. I found through this experience while studying abroad that I could find the sense of awe and wonder for myself, that I didn’t need a professor to tell it to me. Rather, reading, interpreting, and making meaning for myself through these texts could produce that same sense of awe and wonder. Thus, when I teach today, I aim to help my students learn to read, interpret, and discuss texts for themselves. I know that not everyone will find that spark of awe and wonder, but I still aim to provide them with an opportunity for it.

Leave a Reply